The pioneering composer, pianist and educator Muhal Richard Abrams died on Oct. 29, at 87. Among the many artists who considered him a mentor are pianist Adegoke Steve Colson and vocalist Iqua Colson, who are spouses as well as musical partners, and coauthored this tribute.

The 1960s were a time of upheaval, with many pushing for changes in the status quo. In this climate Muhal Richard Abrams, Jody Christian, Phil Cohran and Steve McCall formed the Association for Advancement of Creative Musicians on Chicago’s south side. The idea was to develop and promote musical growth and intellectual thought. By gaining a charter and bringing formality to the idea of a collective, these founders opened a new realm of activity for musicians, dancers, and other creative and progressive souls.

Muhal, Steve McCall and Fred Anderson first showed us the potential of the collective. By the AACM’s seventh anniversary, Adegoke was a member. Within two years Iqua applied and was voted in. As artists with an activist mindset — and some significant efforts at social change under our belts — we embraced the AACM as a revolutionary act befitting the times.

One beautiful aspect of the early AACM was that we met every Saturday. After a review of pertinent business issues, we discussed musical concepts and theories, often going to the blackboard to illustrate examples. History, composition, technique, alternate notation; stories and music all intermingled. All ideas were important. Muhal was a significant force in this, always generous with his contributions.

Everyone from that era had an AACM membership card signed by “Mr. Secretary,” John Shenoy Jackson, a mainstay in the organization. Muhal’s signature, as Chairman, is on Ade’s card. Iqua’s card bears George Lewis’ signature as Chairman. Shortly after George’s term, Ade became Chairman. During the “second wave,” as our generation was called, we hosted conferences and festivals presenting the entire AACM membership, attracting audiences from Asia and Europe. The vision was taking place on the south side of Chicago, and it spread through the city. Muhal and the early members began traveling more, building an international reputation from New York to Paris and beyond. Soon we began to perform outside of Chicago as well.

A structure had been laid that helped further our goals in the multi-tiered music world. As members, we represented ourselves, produced and publicized our own events, and some of us recorded and released our own work. The AACM was an indie movement before that ethos was au courant. Our mantras were (and are) “AACM - A Power Stronger Than Itself” and “Great Black Music: Ancient to the Future.”

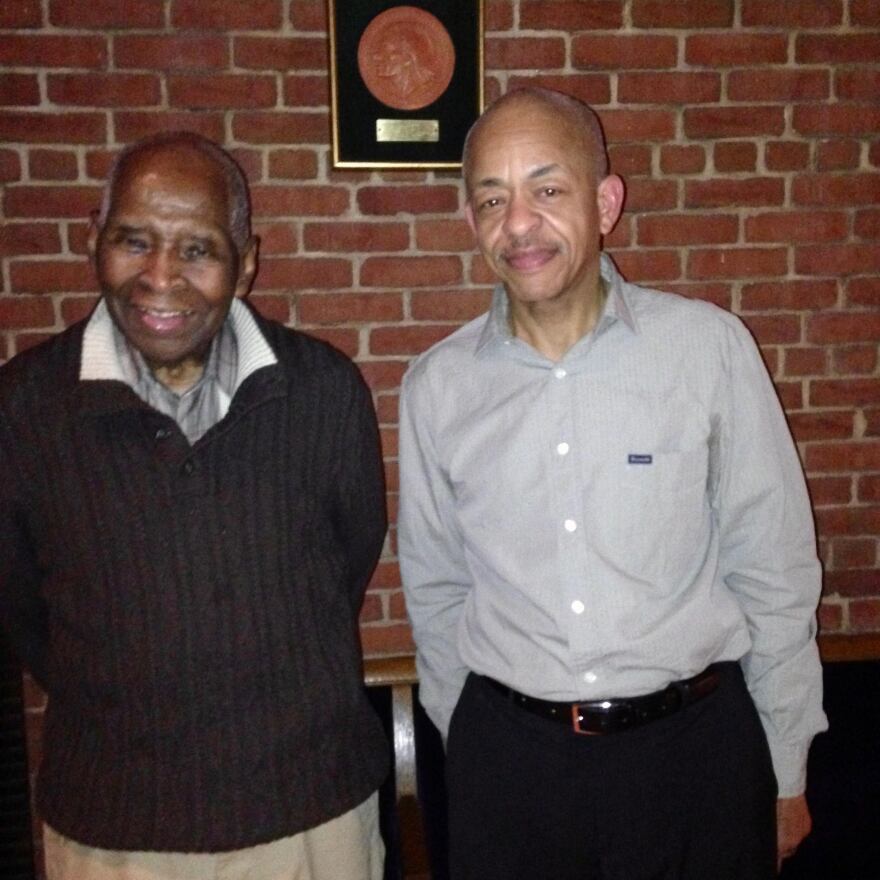

Muhal was always interested in us as individuals and as artists. He knew we had entered Northwestern University’s Music School as pianists, though Iqua was focused on singing. He wanted to know about our studies. He led by example in his personal life, often talking to us about the ways we were working together in this music and raising our two sons. He was at our performances, always telling us to keep going.

When Muhal’s wife and daughter called to inform us of his death, they said “We are calling the family.” We understood the significance of their words. We are family. Though Muhal influenced many artists, we can look back at an intimacy, camaraderie and commitment to purpose that was at the foundation of our relationships from the early days of the AACM. Generations who have grown out of the Chicago chapter continue to show the wisdom of that decision in 1965. Those of us who have known each other for 45 years or more have many stories to tell. And much of the “glue” holding all of it together was Muhal himself.

Remembering those personal interactions helped us process our thoughts. This great and influential musician, composer, bandleader, organizer, friend and mentor had passed away. He died on a Sunday — the day of the Sun — but that would be the perfect day to receive him, for Muhal Richard Abrams was, and will remain, a great blazing star in the musical firmament.

He went beyond any dissension, beyond rhetoric, beyond the divisions. His wide vision allowed him to see that we needed a place from which to launch our individuality. He said the strength of the AACM was our unity in perception regarding composition, and our individuality in realization of the tones and rhythms that emanate from our spirit. Putting forward these ideas, and bringing them into being, changed the nature and scope of modern musical improvisation and composition.

Muhal was instructive and supportive. He loved James P. Johnson, Fats Waller, Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus. In fact, he loved many kinds of music: Bach, Beethoven, Monk, Jelly Roll Morton, Art Tatum, Bird. He talked to Iqua about Billie Holiday, and encouraged Ade to study ragtime, giving him recordings. When Iqua found several out-of-print volumes of piano music by R. Nathaniel Dett, Ade took a copy to Muhal, who immediately turned to “In the Bottoms” – a suite that includes one of Dett’s most performed movements, “Dance (Juba).”

Ade spent many hours with Muhal over the years — listening, talking, and playing the piano, both in person and on the phone. They shared in this way, analyzing and discussing many great and influential composers and pianists from all musical genres. The conversations included musical examples, historic and modern perspectives, and compositional systems. Most recently Ade gave Muhal a recording of two versions of Scott Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag.” One featured Joplin himself, performing his composition exactly as notated. The other captured Jelly Roll Morton, in his own flavorful interpretation.

Muhal’s influence had no boundaries: co-founder of Jazz Institute of Chicago, first winner of Danish JazzPar Prize, NEA Jazz Master. He was a man whose actions in professional and private life quell any talk of the “irresponsible Negro musician.” A man who loved his family. A man who composed for major American and international symphony orchestras. A man awarded two doctorates honoris causa. A man who was self-made, and did one heck of a job at it.