Arthur Blythe, whose bracing, gusty sound on alto saxophone was an essential feature of the New York loft scene in the 1970s, and a proud fixture of the post-bop vanguard in subsequent decades, died on Monday in Lancaster, California. He was 76.

His death was announced by the percussionist Gust William Tsillis, a former band mate who ran the Arthur Blythe Parkinson's Fund. Blythe had been living with Parkinson’s disease for more than a decade, but its effects had worsened within the last four years.

Blythe was a commanding figure whose music connected jazz’s root system with its freer outgrowths, seemingly without a second thought. It was implicit in his broad-shouldered tone — “round as Benny Carter, ardent as John Coltrane,” in the words of Gary Giddins — and through the vibrato that often amplified the sensation of fervency. It was also expressed in Blythe’s choices as a composer and bandleader, and in his notable associations as a sideman, with bands like Jack DeJohnette’s Special Edition.

Blythe arrived in New York City from San Diego in the mid-‘70s, already a seasoned musician but not yet a familiar name. He supported his family for a time by working as a security guard, and began to circulate in a network of artist-run performance spaces downtown.

He was known then as Black Arthur Blythe, in an expression of both personal conviction and political urgency, and he fell in with a creative cohort that included his fellow saxophonists David Murray and Oliver Lake, trumpeter Lester Bowie, and the members of Air. He also gradually found steady work with drummer Chico Hamilton and with the Gil Evans Orchestra, among others.

Blythe recorded several albums on independent labels before Columbia Records, under the aegis of Bruce Lundvall, signed him to a deal. His first two albums for the label reflected his split perception as a progressive and a torchbearer.

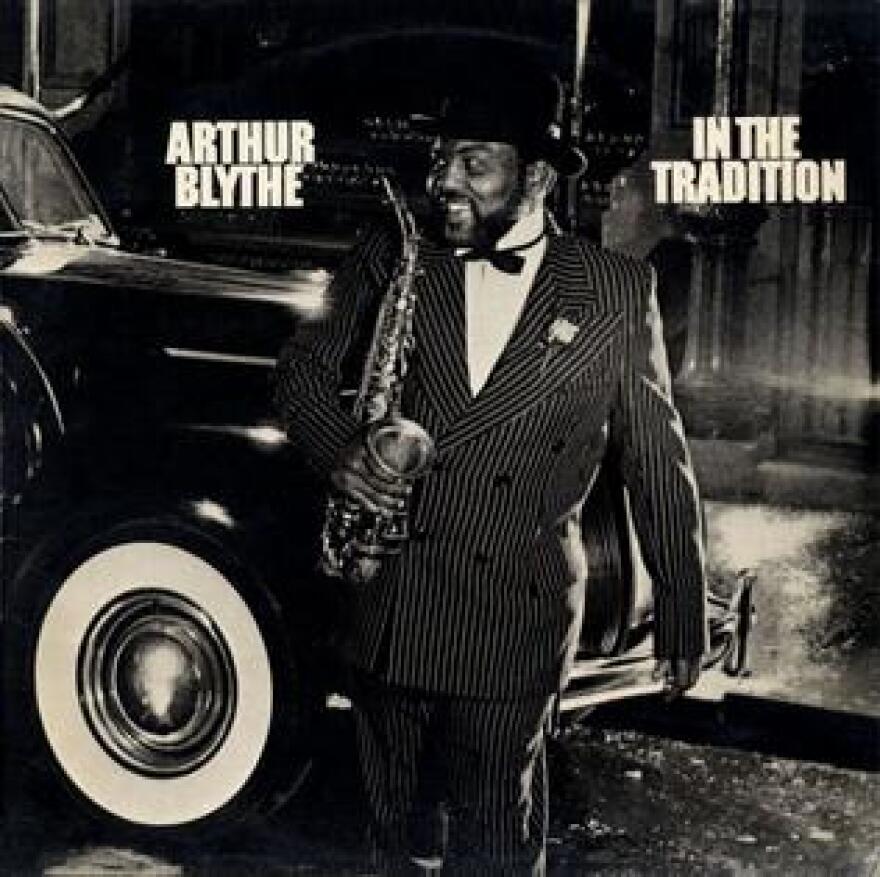

In the Tradition was a stab at radical traditionalism, a program of Ellington, Coltrane and Fats Waller made new by a band that included Stanley Cowell on piano and two-thirds of Air (bassist Fred Hopkins and drummer Steve McCall).

On the album cover, Blythe is depicted in a pinstripe suit and a fedora, in a stylized evocation of Harlem Renaissance cool. The declaration made by the album’s title and attitude later inspired an epic poem by Amiri Baraka; he can be heard performing it https://youtu.be/UgmCpn_jILk">here. (Many thanks to critic Mark Stryker for surfacing the link.)

Still, Blythe’s other Columbia release proved to be the greater breakthrough: Lenox Avenue Breakdown, a funky yet chambereseque outing that featured peers like tubaist Bob Stewart, flutist James Newton and guitarist James “Blood” Ulmer. (DeJohnette is the drummer.) Produced by Bob Thiele, the album engendered a critical response that has only deepened over time. Here is the title track, with a jaunty melodic riff that yields to a cavalcade of solos by Blythe, Newton and Stewart.

Blythe released seven more albums on Columbia before his affiliation with the label ended in the late-‘80s. His visibility dropped off for a while, but he regrouped in the ‘90s, releasing albums on the Enja and Savant labels. He briefly succeeded Julius Hemphill in the World Saxophone Quartet, furnishing a title track for the group’s 1990 Elektra/Nonesuch album Metamorphosis.

And he led his own quartet, in a mainstream vein: Here is a beautifully tender version of Thelonious Monk’s “Light Blue” recorded at the Village Vanguard in ’93, with John Hicks on piano, Cecil McBee on bass and Bobby Battle on drums.

Arthur Blythe was born on July 5, 1940 in Los Angeles, one of three brothers. He had a formative experience in that city’s jazz scene: He studied the saxophone with Kirtland Bradford, who had played in Jimmy Lunceford’s band, and later spent a decade under the wing of pianist and composer Horace Tapscott. Blythe made his recording debut on The Giant Is Awakened, an album by the Horace Tapscott Quintet recorded in 1969.

Blythe’s profile had been quieter in the last 20 years, but he began to enjoy a sort of eminence. He is proudly featured on Down Home, a 1997 album by drummer Joey Baron, alongside bassist Ron Carter and guitarist Bill Frisell. He plays a similar role — standing alongside his fellow altoist Maceo Parker — on Soul Manifesto, a 2001 Blue Note outing by guitarist Rodney Jones.

In 2002, when Blythe released his album Focus, Giddins hailed his return to top form with a feature article titled “Black Arthur’s Return.” Several years later, Blythe headlined a week at the Blue Note Jazz Club with partners including Ulmer, organist Dr. Lonnie Smith and tenor saxophonists Dewey Redman and Ravi Coltrane. (I experienced two nights of the run.)

Blythe is survived by his wife, Queen Bey; two sons, Chalee and Arthur, Jr.,; a daughter, Odessa; a brother, Bernard; and two half-siblings, Adrich Neal and Daisy Neal.

Fond tributes have been circulating on social media, from musicians who knew and admired him. Lezlie Harrison, a seasoned jazz vocalist and WBGO announcer, was a close friend, and shares her recollection below.

Remembering Uncle Arthur

By Lezlie Harrison

When I received the news of Arthur Blythe’s passing, the sadness was immediate and heavy, and I was flooded with memories.

I was first introduced to his music through the 1979 album Lenox Avenue Breakdown, which was in heavy rotation on the jazz programs at U Mass Amherst’s radio station, WMUA, where I hosted my first radio show. After taking an on-air job at WBGO as an on-air announcer — hosting a Saturday evening program called The House Party — I had access to the New York City jazz scene and its practitioners, like Olu Dara, David Murray, Lester Bowie, Kelvyn Bell and Cecil Taylor. And Arthur Blythe.

My friendship with Arthur grew while checking him out at Sweet Basil’s and various other venues around the city, where the hang included cats like Fred Hopkins, Bobby Battle, and Bob Stewart. I got to know him further as my wise counselor — Uncle Arthur — when I became his downstairs neighbor in an apartment building on Riverside Drive in Washington Heights. We shared dinners there, and I babysat for him and his then-wife, Peggy. We were family. I’ll never forget the guidance, wisdom, jokes and gentleness he imparted to me as a young woman out here in and on the music. Arthur offered that beautiful smile and some down-home wisdom about staying the course and remaining humble.

When we opened the Jazz Gallery on August 1, 1995, at 290 Hudson Street, our inaugural exhibit was a tribute to the Tin Palace, a venue I’d never had a chance to visit. I knew about Arthur’s association with it by way of the Gallery’s founder, Dale Fitzgerald. We both unanimously decided that Arthur Blythe should be the first to bless our musical art gallery. On opening night, my friend Arthur — along with flutist and visual artist Lloyd McNeill (designer of the Jazz Gallery logo) — provided the music to a dream come true. That big sound and even bigger heart will remain as precious memories.