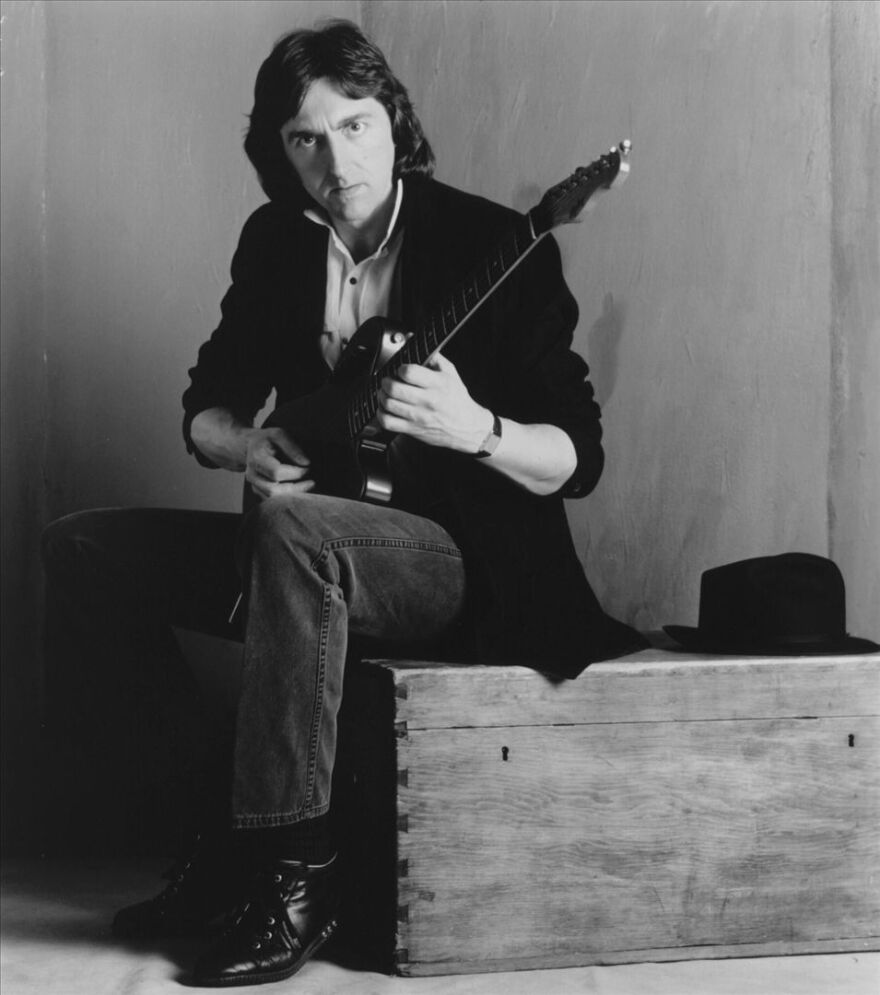

Allan Holdsworth, a spellbinding guitarist who influenced generations of jazz and rock musicians with his innovative sound, has died unexpectedly at age 70.

His daughter Louise Holdsworth announced his death on Sunday, prompting an outpouring of grief as well as high praise for an artist who not only changed the guitar, but also created a musical language entirely his own.

Holdsworth emerged as a promising and original player in the late 1960s and early ‘70s. But he hit his stride in the mid-‘70s, with sideman appearances in major groups on the jazz-fusion and prog-rock circuits. He succeeded John McLaughlin in a new incarnation of the Tony Williams Lifetime, and also worked with Soft Machine, Pierre Moerlen’s Gong, and fusion violinist Jean-Luc Ponty.

His late ’70s collaborations with drummer Bill Bruford (of Yes and King Crimson fame) proved especially strong: Bruford’s albums Feels Good to Me and One of a Kind find Holdsworth in wizardly form both as a soloist and a cog in a bracingly tight ensemble. Holdsworth also joined Bruford (and the late John Wetton) in the supergroup U.K., issuing one of the landmark guitar solos of his career on the track “https://youtu.be/hMu7XUc9OcI">In the Dead of Night.”

The first studio album credited to Holdsworth is Velvet Darkness, a raw jazz-rock outing released on CTI in 1976. Holdsworth took pains to disavow it, maintaining that the session tapes were from a rehearsal, and released without his permission. He made his proper debut in 1982 with I.O.U., and was soon winning ecstatic praise from Eddie Van Halen, among others. In Holdsworth’s liquid, legato line playing, Van Halen no doubt heard a combination of blinding speed and patient, highly musical phrasing, not to mention a harmonic language like no other.

https://youtu.be/RfHJYBBZ7zI">

Holdsworth’s unusual scale runs brought a whole new perspective to the fretboard; they were colored by rock distortion but had an almost flute-like beauty. Jazz guitarist Kurt Rosenwinkel, in a 2005 interview with this writer for JazzTimes magazine, said this of Holdsworth:

To me, he’s the only guitarist dealing with the kind of language Coltrane was dealing with — those long Slonimsky patterns that evolve differently through different registers in a very precise way, but pure like a prism. That’s a big part of what I hear, that clarity of harmonic unfolding and melodic intricacy.

Holdsworth’s chordal language, in its sheer imagination and otherworldliness, set his music even further apart. Unlike the solos, the chords were voiced with a clean, glass-like reverberating tone. They involved extreme finger stretches required in no other kind of music. They brought out strange intervallic combinations: on “https://youtu.be/K_pJIWC58uA?list=PL_ckEpFj54EZFAXYkBo7IVMqsuM1jb8S2">Looking Glass,” from Atavachron, two notes on the lowest strings and two on the highest strings, with nothing in between. Reaching for the Uncommon Chord was the title of a 1987 book of Holdsworth transcriptions, and for good reason.

While Holdsworth’s music could produce searing heat (hear “Peril Premonition” from Secrets), it could also be disarmingly tender and intimate: His acoustic guitar solo on “Home,” a lyrical ballad from Metal Fatigue, is arguably one of his finest moments. He went after all kinds of sounds, famously experimenting with a guitar synthesizer called the SynthAxe, now consigned to the ‘80s dustbin but not without its wickedly surreal qualities.

He also attracted musicians of supremely high caliber, and they stuck with him — electric bassists Jimmy Johnson and the late Dave Carpenter, drummers Gary Husband and Chad Wackerman among them. Husband, also a fine pianist, recorded a solo piano album in 2004 called The Things I See: Interpretations of the Music of Allan Holdsworth. In its speculative abstraction, it shows how Holdsworth’s compositional muse can transcend the guitar and form its own universe.

Born in Bradford, England on Aug. 6, 1946, Holdsworth was schooled in the fundamentals of music theory by his father, an amateur musician. Among his early jazz-guitar influences were Joe Pass, Django Reinhardt and Charlie Christian. He was working widely on the club circuit in England by his 20s, catching the ear of tenor saxophonist Ray Warleigh, who brought him into the jazz scene, at places like Ronnie Scott’s.

Holdsworth never stopped touring and recording, and had been in the midst of a creative resurgence roughly since the release of his 2000 album The Sixteen Men of Tain. Earlier this month, Manifesto Records released a 12-CD boxed set titled The Man Who Changed Guitar Forever, as well as a new best-of collection, Eidolon.

Holdsworth is survived by three daughters — Lynn, Emily and Louise — as well as a son, Sam, and one granddaughter. He was married twice; both marriages ended in divorce.

In the hours following Holdsworth’s death, tributes came in from guitarists including Steve Lukather, Vernon Reid and Joe Satriani. But not just guitarists: Pianist and keyboardist Geoffrey Keezer called Holdsworth “one of my biggest musical heroes, and a true unsung genius of our time.” Drummer Vinnie Colaiuta wrote that playing with Holdsworth was “a major highlight of my musical life.”

Rosenwinkel’s Twitter tribute was particularly moving:

Allan Holdsworth, Colossus, gentle man, blazed a trail through the heights of musical invention. we can only look up & marvel. God Speed RIP

— Kurt Rosenwinkel (@kurtrosenwinkel) April 17, 2017